- Home

- Channer, Colin

Iron Balloons Page 8

Iron Balloons Read online

Page 8

But anyway, I wasn’t really paying them any mind, you know, because I’m not a person that like to put myself in people’s business. Plus, I was in a mood where not a thing was going to bother me, because I was coming from a luncheon for my daughter Karen. I can’t really remember the place. Fancy place though. When you walk in there you see class. What it name again? It has a name like a person. But for the life of me I can’t remember what. Fancy name though. French.

But anyway, a lovely place though, down Wall Street with plenty columns and chandeliers. Her office give her a big honor today, that’s why you see me dress up like this, with my hat like I going to church. Cause you know me. I’m simple. I don’t like fuss.

But anyway, when I reach the register now, the mother and the daughter come up behind me, and the arguing was still going on. Just bloo-bloo-bloo-bloo … bloo-bloo-bloo-bloo… mother and daughter back and forth, and my poor ears couldn’t eat grass.

So when I sift through all the bloo-bloo-bloo, I pick out that the little girl get into bad company. She won’t do her school work or go to school, and the mother went up to her school to talk to the guidance counselor, and the little girl tell her off. Tell her off in front o’ the guidance counselor, the principal, and her English teacher. Denounce the mother and call her all kind o’ names.

So this is what the mother was trying to talk to her about in the pharmacy now, when the argument start.

Some things the little girl tell her mother I couldn’t even say in class. No child suppose to say those kinds of things to their mother. When you look at the little girl, you know, you can see that deep down she is a nice little child. But nothing more than she feel she big now because she turn seventeen, so her mother mustn’t say nothing to her. When I tell you, nice looking girl too, you know. Small in body but you can see she have a nice shape. She have hips. And her hair is so tall and nice. Tall down almost to her bottom. And when you talk about wavy and thick. And don’t talk about shine. And to top it off, she have a beauty spot on her cheek beside her nose. Have an Italian look. Pretty girl in her green plaid uniform, so you know the mother spending money to send her to the good Catholic school. But just out of order. Just out of order. Just out of order. And rude. Just calling her mother stupid and denouncing her how she don’t know anything, and shouting after her how when anything happen she always take the guidance counselor and the teacher side.

When she say that, you know what happen? I feel like turn around to her and say, Whose side she suppose to take? She’s your mother.

But I keep my mouth shut.

So anyway, I couldn’t get the little girl and her mother out o’ my mind even after I leave Duane Reade. But I had a lot o’ time before class, so I went to get me exercise—you know, walk around.

That is how I keep myself fit, you know. I like to walk. That’s how come I don’t move from one thirty-five from I come to this country. I lose a little o’ the height though. You know, the bones and age. But I born with height to give away.

By the way, when I say I like to walk, that don’t mean I like to walk any and anywhere, you know. I don’t like to walk in parks and all that kind o’ thing. I like to walk in Manhattan. I like to walk in the city. While I walking, if I see anything for my children or grandchildren I can stop and pick it up. Or if I want some tea or something to eat, like for instance if I get some gas, I can stop and take my time, then start to walk again. Plus, when I watch New York 1 I hear ’bout too much women who get rape off while they exercising in the park in broad daylight. I don’t know why they bother go and tempt fate for. You think is yesterday man like to rape woman in bush? So you know this now and going to go out and run beside the bushes with you leg expose in shorts? Listen to me, I never once hear ’bout a woman getting rape in front o’ Rockefeller Center at half past 12. So what that tell you? Stay with the crowd!

So anyway, Wall Street is one o’ the areas where I like to walk. Down there is like England to me. You have your little streets and your old white buildings. And almost anything you want to shop for you can get down there. Plus, is a orderly kind of place. Is a business place. Down there, you don’t have nobody running up and down like they wild. Take for instance Times Square or further down where I work in Herald Square—too much wildness up there, man. Too much young people idling with no ambition or nothing to do. Just running ’bout the place and talking loud. If they bounce you by accident, they wouldn’t even say, Excuse me. And when they ask you a question is like they don’t know the word please. But sometimes you can’t really blame them. When children come like that, is the parents’ fault.

Speaking of fault, you know if they don’t organize a luncheon for me at Macy’s, is my fault. As I mention Herald Square I remember that this month make it thirty years since they took me on. If they know what I know, they better have a luncheon for me like my daughter office had for her this afternoon. Even if is just accounting alone. Or is hell to pay!

But anyway, when I say I couldn’t get the girl and her mother out of my mind, it was the mother I couldn’t forget, in truth. And when I walk about two blocks I start to hear a voice telling me to turn back. And I kept telling the voice that is not my business. But the voice wouldn’t stop, and all the fight I keep fighting it, you know what I do? I spin round and turn back down to Duane Reade.

The way I was stepping down Broadway, people must be think I was mad. Because you know how down there stay—everybody moving like they have battery, or somebody wind them up. Just voom-voom-voom-voom … voom-voom-voom-voom. Worse, is summer, so all the tourists come and make the place more pack. And they don’t know how to walk.

So imagine my dilemma now. You know how the sidewalks down there stay. Hardly two people can pass. And is me going one way, and is them coming the other way. And is me boring through, and is them getting mad. But I don’t care, because I had to talk to that mother. I had to talk to her. Because when I take a stock, I realize that her hands were so full and she don’t know what to do.

And … hmm … let me tell you …

Hmm … ahh bwoy …

You see my daughter Karen, who I went to the luncheon for? She might be a Senior Vice President at JPMorgan Chase now, but don’t think it did always look like she was going to turn out the right and proper way. At one time it look like she was heading for the gutter fast, fast. But you know what save her? I, as mother, did what I had to do. Because, le’ me tell you something, you know: Once they go past a certain point—these children?—don’t think it easy to bring them back. When certain kind o’ rudeness come, you have to nip it in the bud. When they want to spring up like they fertilize themselves and act like they big, but you know for a fact that they small, don’t wilt in front o’ them. Stand up firm! Hold your ground! Push them back. Sink them down again below the grass, and stand up over them like you have a machete in your hand. If they push up they head again before they time, don’t hesitate. Take one swing and chop it off.

So anyway, when I reach by this big store here … the one where you can buy everything from clothes to luggage but your mind always tell you to really look ’pon the label good—Century 21—I think I glimpse the two o’ them, and I stop to focus. And you know what? It was the two o’ them in truth.

When I almost reach them now, I call out to the mother.

I say, “Excuse me, miss. You were in Duane Reade?”

I could touch her on her shoulder, but I don’t like to touch people in this place. Since 9/11—especially down that side—everybody get extra jumpy, m’dear. Next thing, you touch somebody and them turn round and think is terrorist and shoot you.

So, when I call her now, the mother stop and look at me and say, “Yes. Is something wrong?” She must be see a little thing in my face. Cause I’m a person like this, you know. I can’t play hypocrite. And I can’t take hypocritical people. I’m like Flip Wilson. What she name again? Geraldine. Don’t you cry and don’t you fret, cause what you see is what you get.

Anyway, the mother ha

d on a tan coat that catch her to her knee. Not a dark tan, but more like … you know those Clarks shoes? Same color as these chairs here you sitting on. It was a spring coat with a belt round the waist, and from I see that I know her dress was not in good condition. Because now is May, and is just too hot for that. Plus, she didn’t polish her shoes. Some twenty-dollar pumps. And the shoes itself was lean.

And when I see that now, I say to myself, Dear God. Imagine, this woman sacrifice for this child so much and this child treat her like dog mess. The parents who do the most get the least thanks.

Breeze was blowing. And like how they don’t have the World Trade Center again, it was coming right through … whih-whih-whih … from over by the Westside Highway. I had to turn my back and take off my glasses before it blow off. For if it blow off, is me same one have run it down, and next thing dirt blow into my eye and blind me.

You’re laughing. But is true. You can’t take any chance again, you know. Not when you’re old. I accept that fact. When the breeze start, I say to myself, Glasses, hat, and frock. You wondering why I say frock? Heh! People nowadays wi’ scrutinize you same way. No matter how you’re old.

So anyway, I ease over underneath one o’ the awnings down by Century 21, and the mother and the daughter follow me. And when I straighten out myself now, I say to the little girl, “Sweetheart, I overheard you in the Duane Reade. Why you talk to your mother like that? I can see you’re a nice girl, from a decent home. Look how your mother work and send you to school, eeh. And look how your uniform neat and nice. Why you speak to Mummy like that? You not to do that, sweetheart. When you talk to Mummy like that, you will make her feel embarrassed, like she don’t train you at home.”

That little wretch! You think she pay me any mind? No sir. She just take her mother hand and say, “Come on, Ma. Let’s go.”

But is like what I say gi’ the mother a little choops o’ strength, and she pull her hand away from the girl and wipe her face. But still yet, when she talk to me, her voice sound like she can’t mash ants.

Hear her: “She’s going through a very hard time.”

So I say to her, “Ma’am, I understand. But you’re her mother. No matter what she going through, she must know she can’t talk to you like that.”

When I say that now, you know what the little girl do? She fold her arms and whisper, “Mind your effin’ business.” And believe you me, she didn’t say “effin’.” She said the actual word. When she say this to me and done, she turn to her mother and say in a kind o’ tired voice, like she’s the one suppose to be frustrated, “Let’s go.” Then she swing herself and walk off.

And believe you me, the mother was going follow her.

When I see that, you see, I grab onto her hand and say, “Don’t follow her up. Don’t follow her up. Make her go on. Make her go on. If you follow her up, all you going do is make her think she can lead you. Don’t make that child lead you like she have you on a chain. You’re a woman. She’s a child.”

Now, you could see the mother know it was sense I was talking, you know, but she so accustom to making the child treat her like a little puppy, that she start to whimper now, “Jessica. Jessica. Jessie. Jessie. Come here. Come here.”

And you know, the little demon never even look back at her mother and say, Yes, dog?

When the daughter pass and gone round the corner now, I take my other hand and turn the mother face to me. I look at her and say to her softly, cause I know she was feeling the pain, “Look here, miss. I know how you feel. But never mind. Never mind. I go through the same thing, a’ready. She has money to go home?”

She shake her head and say, “Yes.”

“She normally go to school by herself?”

“Yes.”

“And come home by herself?”

“Yes.”

“So let her go on then. Let her go on. Don’t follow her up.”

She cover her face and start to bawl loud, loud now. You could stay across the street and hear. So, I put my arm around her like she’s my friend long time and hush her. And as I hushing her now, she start to tell me how the girl was a nice, nice girl until she turn seventeen last year. After that, she don’t know why, but the girl start to follow some friends into a bad crowd. And now she want everything to be her way. And she not studying her books.

She didn’t exactly say “bad crowd,” but that is what I pick from it. I know how to pick things out o’ things, you know, and how to make sense out o’ nonsense. If you ever hear how much money that mother spend on psychologist! And how she waste the guidance counselor time! When all she had to do was what she as a mother was suppose to do. But I know why she didn’t do her duty. She ’fraid.

Anyway, as I’m listening to her now, I realize that when I thought she and her daughter was Italian, I was wrong. To tell you the truth, I can’t tell you exactly what she was. But is not Italian. She look Italianish though, and she had a funny accent. But Italians in they forties not coming to America again, like one time. And you could tell how her accent thick that she didn’t live in America long. Plus, I know Italians. I live with them.

When I just come to America in 1976, is mostly Italian use to live near me, you know. That was up in the Bronx … up by Boston Road and Eastchester Road there—3678 Corsa Avenue, the first house I own in this place.

Serious as a judge. You might see mostly West Indians up there now—though I hear a lot o’ Hispanics moving in—Lord Jesus. But it was pure Italian up there in my time. Even now, out in Long Island where I live now, guess what? I buck up on Italian again. Is like they love me. Perillo one side! Moretti next side! Polish in the back.

So when I say the woman wasn’t Italian, I know what I talking about. But you could tell she was some kind o’ cousin to them though … something from round that side. I’m not so good with the European setup, so I can’t tell you where exact. But that don’t mean I don’t know the continent though, you know.

My son Andrew, the one who follow Karen—the bond lawyer—he must be send me over there about six or seven times a’ready. Everything first class! But I didn’t go where use to be the Communist part though. And I think she’s from over that. Listen to me, Communism come in like germs, you know. When you think it gone, it come right back and hold you. And when you think you have the medicine, it change on you. It evolve! Look at Russia. They say they free, but is Communism still. Can you imagine if I go make my son pay for me to go over there and something happen to make me can’t come back? What I would tell Mr. Macy’s Monday morning?

Thirty years at Herald Square, and never missed a day! Never been late! Perfect record. Thirty years! That’s why I can do as I like up there. They don’t bother with me. You know why? I’m a dedicated, disciplined worker. And these days especially, when workers like to jump from place to place, you can’t beat that.

So anyway, as I said, they wasn’t no Italian. But Italian was never the point. Here was a mother in distress. And this was a distress that touch something in my mind. As it touch me now, I told the woman that I went through the same thing with my daughter Karen, who is older than her. The woman, as I said, was in her forties. Karen must be fifty now. For I’m sixty-eight.

“You see, when they get like that and you try with them,” I say to her, “and you keep on trying with them, and they still not hearing, is only one thing left to do. You have to beat they ass. Don’t make America turn you into any fool. You don’t come from here. As there is a God in heaven, when children—especially girls—start to act a certain way … like they is equal to you … you have to put them in they place. And don’t make them or anybody else frighten you ’bout police and child welfare and all o’ that. If you know exactly how to beat a child—call the police? You mad? After what they get from you?

Hmm … they wouldn’t dare!

When the woman run off screaming down the street, a voice say to me that maybe I didn’t really bring my point across. Maybe I didn’t fully explain the whole thing with the police. So I start

to think how when you look at the state of young people in this country today, there’s a lot of parents who could benefit from knowing how to grow their children right. What to do when they start to bend away from how they brought them up. How to grab ahold of them and straighten them out.

So it’s this voice and this incident, my fellow classmates, that made me change my speech from “How to Make a Budget and Stick to It” to one more beneficial to the world these days: “How to Beat a Child the Right and Proper Way.”

By the way, professor, I see you giving me the signal that I’m over my time, but I should point out to you that neither Singh nor Avila nor Cumberbatch are here this evening to give their presentation, so you might as well give me their time. And look. See, everyone agree. Why you think they clapping for?

So, Professor Hansen and considerate classmates, to understand why I behaved the way I did today you have to understand a little bit about my life.

I was born in Jamaica in 1938, and although you mightn’t believe it, when I was coming up I was very poor.

My mother and father had eight of us. My father was a postman, and my mother use to work in a sweetie factory, making lollipops and bubble gum. When you have those kinds of work in Jamaica, especially in those days, things was very hard. It’s not like up here, where if you are a postman you can live a decent life. Down there they use to pay the postman like he was a child riding a bicycle and all they had to do was give him pocket change. But he use to have to pedal round the city in the heat with pounds and pounds of mail.

So when you see me now, don’t grudge me. I’m coming from very far.

Now, the house where I grow up was at 2a Saunders Lane in East Kingston. It was a board house, a rent house. It was smaller than this trailer here. By the way, professor, I can’t take this room. It make me feel like I waiting for bail. Anyway, all of us live in that one-room house. But you know something? We keep it clean.

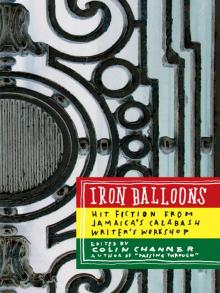

Iron Balloons

Iron Balloons