- Home

- Channer, Colin

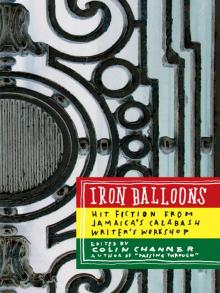

Iron Balloons Page 6

Iron Balloons Read online

Page 6

And even though they’re only words, it’s like a needle jooking you. Jooking a hole in the incredible bubble of the story you have in your head, and so now you feel all the wanting-to-tell-it come hissing out, and you feel the story shrivelling up and folding away.

You pass him the stupid socket and then you run across the yard and jump on your bike and ride through the gate in so much vexation you don’t tell anybody anything.

If it was daytime you would ride into town and ask the lady at the library who stamps books and knows everything if there isn’t someplace you could go to complain about the family you are in.

You ride until you realize it’s too dark to ride. This realizing it’s too dark to ride occurs at the same time you feel yourself flying because the bike realized, before you did, that it’s too dark to ride and it stopped this riding-in-the-dark stupidness before you did. So now you are flying, and flying would be okay if you didn’t already know that at the end of flying is bush and macka and pain.

The bush comes with a oorphrumph sound. The macka comes with a eeeyii sound. And the pain—the pain calls down all kinda bad-word sound that you didn’t even know you knew. But you do, and you holler them out like any old drunken man on a Friday night.

There is something about pain that makes you feel for home. Makes you forget how much complaints you have against your family and you just wish you were in the arms of your mother with her hands fixing up your broken body, with tenderness in her eyes and a worryness on her face. She can say, “Nice,” now. She can say whatever she likes. You don’t mind. Pain can make even “Nice” sound like something someone could say. Pain is like that. Pain is also like a worm chopped in two. It has a furious rolling and wriggling around in it and a crying for its mother in it.

You don’t know about your father coming for you.

You don’t know about him carrying you like you are two years old all the way back to the house or about your sister wailing when she sees you in his arms with your leg looking like it has been put on back to front, inside out, upside down.

You just know that this place, this bed, is not your place, not your bed. And when you try to move, you wonder if this is even your body. Your whole body feels mashed like pounded yam and your head is a fish swimming around and around and around in a bowl.

You try to sit up, and that is when you notice that you cannot sit up because of your leg. It feels like it is in concrete. Your head is still spinning so you have to ease up carefully. Someone has put your leg in concrete, and around it is wire and pulleys like you are a machine. Slowly you begin to understand what has happened—they’re turning you into a machine. Mary Janga’s people have come for her and taken you instead, because they want to turn people into robots. And who with any sense in their head would take up Mary Janga when they could take you?

You have to escape. Just as soon as your head stop this spinning t’ing, you will escape, you tell youself. You tell youself you will lie down for just a minute and then you will escape. You will lie down and close your eye for just one second and then … and then … and …

A big face is smiling down at you. It doesn’t look like an alien face. It looks like a normal somebody’s face. It is smiling but you don’t smile back. You know you are in mortal danger of being turned into a RZ105 or something like that, with numbers and letters for a name. But the more you look, the more this face begins to look just like somebody you know. The face begins to be the face of Nurse Lawes.

The face says, “So how you feeling? You take a bad fall, y’know.” (This is just the sort of thing Nurse Lawes would say.)

When you try to lift up, the Nurse Lawes face says, “A’right, take it easy. We have yuh leg in traction.”

You wonder what your leg in concrete has to do with ploughing up land, but you figure tractors are big machines and your leg is like a machine, so maybe they correspond. You don’t say anything. You just nod. Aliens can be funny, you tell yourself. Nodding is best.

Next thing you know, she’s lifted you up with one hand, and with the other, she’s organized the pillow into a back rest so you can sit up. You sit up and look around and realize that, guess what? Nurse Lawes is Nurse Lawes, because guess what? You are in the hospital. All around you are beds with children in them or not in them. Some children with bandages on their heads or around their arms are sitting in a corner watching TV and some are playing together with toys on the floor and some of them are reading books and some are just lying down still, but all of them have on pajamas.

Nurse Lawes tells you she is going to bring you a drink. You watch her walking to the end of the room. You want to call her back and tell her that you don’t want a drink, you want to go home. You want your mother; you want your father. You even want Mary Janga. But you feel too shame to shout these things out and so you just think them to yourself. And while you are thinking these things to yourself, you start to think about what happened to put you in this bed that is not yours, in this place that is not yours. But all this thinking starts your head spinning again and you have to close your eyes.

In the darkness behind your eyes, you try to remember without thinking, but nothing happens. If your memory is a computer screen, it is blank. If it is a box, it is empty. If it is a sound, it is silent. You start to feel scared. You feel just like when you were seven and you went to cricket with your father and he told you not to let go of his hand, but instead of not letting go you let go because you were too big to be holding his hand. And so you let go, and in that second his hand, his arm, his whole body disappeared, and instead of it being you and your daddy at cricket, it was just you. You and millions and millions and millions of arms and legs and bodies you did not know. And you felt alone and scared, just like you feel now, because here you are in this strange place and the only person you know has gone to get a drink you don’t want.

Your body is turning into a robot. Your head is a spinning top and your memory is an empty box, a blank screen, a silent sound. You feel all alone and … but wait! You do remember something. It’s not the something you want to remember, but it is something. The cricket story is something. And your father and your mother and Mary Janga. They are somethings too. You don’t feel so bad now. Not so, so bad, but there is still some feelbad in you because yuh mash up and alone. The only thing you can think to do is pray and so you do.

Just as you finish praying you hear swoosh … swoosh, and you see Nurse Lawes coming back through the big plastic doors at the end of the room. The doors make that sound—swoosh … swoosh—when they open and close. Before she gets to your bed with the drink, you hear swoosh … swoosh again, and you think you see a little girl in a jeans skirt and a pink top come running in. Yes, it’s a little Mary Janga girl in a pink top calling your name in a loud, screechy, excited voice that does not belong in a hospital.

Sometimes it takes a long time to get an answer to a prayer. Sometimes it can happen before you even finish praying and sometimes the answer comes and it makes you feel shame. Mary Janga calling out your name in that voice that belongs somewhere far away from here—somewhere where nobody can hear it—is an answer that makes you feel shame. But mix up with the shame is a smile and a gladness, and when the doors go swoosh … swoosh again, you know you don’t even have to look up.

Your mother has brought you mangoes and bananas and June plums. Her eyes look like they want to cry and she keeps stroking your head. She tells your father to sit down instead of pacing backwards and forwards like that, but he doesn’t. He keeps on pacing and shaking his head and saying, “Bwoy, me no know wha’ ’appen to dis bwoy. Wha’ de hell get into dis child? Eeh?” And you wish he would sit down because he is making your head spin again with all the up and down he’s doing.

Mary Janga gives you something in a brown paper bag and then she drinks off all your drinks without asking, “PleasemayI?” and then some madness flies up into her head and she pounds on the concrete around your leg like she is pounding on a door.

Your c

rying-out-in-pain voice is even louder than Mary Janga’s voice, and everyone in the room looks at you like you have something to tell them. Nurse Lawes comes for Mary Janga. You think, Maybe they’ll operate on her straight away and take out whatever it is that is in her that makes her so … so … Mary Janga.

Then your father does sit down, and straightaway you wish he was standing up and pacing around, because as soon as he sits he has more questions—questions you cannot answer, like, “Bwoy, wha’ ’appen to you?”

Questions like, “But whe’ de hell you t’ink yuh was going dem kinda hours deh?” And, “So yuh never hear me a call to yuh? So yuh tu’n big man and cyan do wha’ de hell yuh like now?” Questions that nobody in the world can answer like, “Eeh? Eeh? Eeh?”

And then your mother asks you the most difficult question of all: “So yuh ’member wha’ happen to yuh?”

You shake your head and tell her that you don’t remember one thing. And the moment you shake your head, it starts to spin faster and faster. It is spinning so fast it is ready to take off. It’s on the runway. It has full throttle, you can hear the engines roaring, the engines roaring, the engines roaring …

Yes! Yes! You do remember. Your father with his head in the truck and the engine roaring and “Nice” and “Yuck” and ratchets and sockets and bubbles and … and how could you forget? The most incredible thing in the whole wide world. And the story bubble is big, big, big now, and it is so full of wanting-to-tell that it is ready to bus’, and it does, and so you tell them about the sound that you heard and how you followed it into the bush and how you went softly, softly when you got near because you saw it was a goat. That big fat goat that belongs to Mas’ Arnold in Spring Gully, and how the goat was lying down on her side and crying, “Mmeeeer-mmeeeer,” and straining like she want to doodoo but it wouldn’t come out. Crying and straining and crying and straining and then, how, all of a sudden, this slimy thing like a big piece of Jell-O that someone forgot to color in just pop out, and how you could see something moving around in the Jell-O, and how it had you there like a piece o’ rock just a stand up and a look and cyaah move. And how the mommy goat lick up the bag, lick it and eat it, and then how the thing that was inside come out, and how it was all wet and looking just like a real goat but small, small. And how the mummy goat start lick it now, and how it wobble around like it couldn’t manage to stand up, and then it did and then it start to suck—just like Mary Janga when she was small and still like a human being.

And then you finish and you look up and you see your father, your mother, Nurse Lawes, and Mary Janga with a really-listening look on their face and all the pajama children are around your bed too and now one of them seh, “Fe real?” and another one seh, “Wow!” and then, for just one small moment, there is silence—your father has no more questions in him—not even Mary Janga is making a sound. Everyone has listened to your incredible story. Everyone. It’s amazing. It’s stupendous. It’s … incredible.

It’s night now.

All the parents have gone home and all the pajama children are in bed. You can hear the nurses talking softly and laughing at the end of the room. You can hear the trees moaning and creaking and tapping on the window behind you and you think of scary stories. You wonder how it is that scary stories always seem so stupid in the day but the moment night come down they don’t seem stupid at all. You think they must have some magic in them, and if they have some magic, you think, then maybe they have some realness in them too.

You feel alone and scared.

You don’t want to feel alone and scared. But you do.

You think maybe a mango will stop you feeling like this.

You switch on the lamp next to the bed and then you see the bag Mary Janga left for you.

You open it. Inside is Floppy Florenzo the Rabbit. Floppy Florenzo the Rabbit is lime-green with bright pink ears that glow in the dark. You quickly turn off the light and stuff Floppy Florenzo the Rabbit under the cover. You shake your head and think, That little girl is something else.

Floppy Florenzo the Rabbit smells of Mary Janga on the porch talking to her dollies, and your mother’s tender hands and your father finding you at cricket and carrying you on his shoulders.

You yawn. You feel tired … well, well tired.

Just before you drop asleep, you hear Floppy Florenzo say, “So what? Yuh not telling me goodnight?”

SIBLINGS

by Rudolph Wallace

It start off like a ordinary Saturday morning. Mr. Evans take time wheel him bicycle outta the front room from before 7 o’clock. If anybody ask him where him always go so early, him tell them him go look work. Him a plumber, and him nuh have no tools ’pon him, but nuh watch that. Him two pickney know better—say a more rum him gone drink.

Andre leave out little after 9, gone play football before sun get too hot. Him pass Annmarie inna the front room, a use a old towel sop up the piss ’pon the linoleum floor.

What is there inna this rum thing, my God, that turn big man inna little baby?

Donna come over around 11 figive Annmarie a hand with the big bag o’ peas she get in from country. Donna good with the gungo for she used to sell it too—though she nuh set foot inna Coronation Market from the day she meet this guy Tony two months ago, with the good U.S. dollar like it a come outta him ears. A pure Spanish that talk, y’know. Them coulda barely understand one another, but nuh ask if him never manhandle the body. Three weeks now Donna nuh see him and she still a walk funny … and still a lick out cash.

Donna did wa’ set up Annmarie with one o’ Tony friend, gi’ her a chance fieat a food. But Annmarie very partial when it come on to man—nobody nuh know wha’ she a try prove. One thing Annmarie nuh like ’bout Donna—she chat sometime like them wind her up.

“So Annmarie”—she chaw the bubble gum and wait till Annmarie look ’pon her—“when you a go set me up with Andre?”

Annmarie cut her eye and kiss her teeth. “Me coulda say me love my little bredda and send him figo deal with you, Donna?”

“Wha’ wrong with me?”

“Me nuh wa’ you inna mi family—that a the long and short. Fi one thing, you older than him … and fia next thing, you a go keep man with him. Me know you too good.”

“Suit youself. Is only help me a try help out a situation. You suppose to know say them have it outta street say him gone.”

“You a chat shit.”

“As God.”

The two o’ them position in front o’ one another ’pon the veranda, ’pon either side o’ the washpan with the bitch crocus bag o’ green gungo a them foot—two hours work you a look ’pon at least. And with all o’ that, whenever time Andre name come up, Donna can still find time fidrop her left wrist and flutter her finger them. God—He knows which part she get da move dey from—she mussie know one battyman pianist.

Annmarie nuh take her on more than so. “If any o’ my puppa pickney ever dare talk ’bout him a tun gay, that’s the last word woulda come outta him mouth—me can tell you that fia fact.”

Donna don’t out fiease up. “Gi’ me ten minutes with him and me can tell you if him a battyman, yes or no.”

That blasted rumor. Every time Annmarie think it dead, it appear again—like herpes to rass.

“How come all of a sudden everybody a come to me with some little fuck-up remarks ’bout mi bredda? It look like oonu tired o’ talk it behind mi back, so one by one oonu a test me. Me know what the problem is, y’know. A because him so cool and sexy, oonu vex say him nah look none o’ oonu—that a the one and only problem.”

“Cool and sexy, eh? A so them always cool with woman, but wait so till you see them ’mongst them one another.”

Donna laugh—her loudest market woman laugh.

“Wha’ you see wrong with him?” Is like Annmarie a count her word them. “Oonu can’t say him effeminate nor nutten. A him captain Conscious Youth under-17 football team last year, right? And nobody nuh fight ’gainst battyman more than them dey young boy.�

�

So she talk, she fling peas, trash, knife, everything inna the pan, then get up and shake out her skirt, make sure some o’ the fine trash fly inna Donna eye. Donna make up her face but she nuh say nutten.

Annmarie go stand up beside the veranda railing where Donna can’t see her face.

“You see why me hate Fletcher’s Land people? Oonu brutalize oonu owna kind worse than any Saddam. A nuh no big thing when a seventeen-year-old uptown youth nuh have no girlfriend. But down ya? Unless him a go ’bout the place and boast ’bout how much baby mother him have, everybody start ask question. Oonu nuh business if him have a work or if him can support himself. So longst him a lay down with every frowsy-tail gal inna the community.”

“Annmarie, you a take this thing too personal. A nuh your fault if you bredda touch. My mother have a cousin stay same way. Answer me this one question: If nutten nuh do him, how come him nuh have no girl? Fi him buddy join church?”

“Donna, don’t you say you come over ya fihelp me shell the peas? Then make you nuh bruk down the almshouse argument and shell the bumboclaat peas?”

Same time Andre come through the gate, soak with perspiration. Him T-shirt fling over him shoulder and all him have on is a shorts and him football boots. Him coulda never did pick a worse time.

Donna pounce right away. “Come ya little bit, young boy. Wha’ you a do Friday night?”

“Friday night?”

“Yes. Them a keep a dance down a Nova and me have a nice girl fiyou.”

Andre, who-for spirit never too take Donna from morning, barely slow down fianswer her. “I mighta pass through if I have the time.” Him fake fithrow a punch after Annmarie and she gwan like she duck it, then him skip go inna the house.

Iron Balloons

Iron Balloons