- Home

- Channer, Colin

Iron Balloons Page 18

Iron Balloons Read online

Page 18

A lizard, the color of many rainbows, slithers by on the ground. I hand Ma the bulging envelope, from which I have removed a couple of the Yankee hundred-dollar notes for myself that I will hide in a secret place, beneath a loose floorboard in a corner of the dining room. The rest of the money in the envelope will keep my mother and my sisters and brothers fed and clothed for a while.

“I had to work two shifts.” I say the lie with a smile. “I made some extra.”

She looks suspiciously at me before snatching it away with a soapy hand, tucking it into her bosom. “Just thank God that you get that job over there at the hotel,” she says, resuming her washing. “You lucky.” She slaps at a mosquito on a varicose-veined leg and begins to hum the melody of a hymn she sings at the clap-hand church she visits on Sunday mornings. She does not say another word to me.

Again, I am dismissed.

I turn and walk toward the crumbling little house, with its leaky roof and rickety floorboards, hearing the words of the hymn trembling in the air.

A mighty fortress is our God …

I can see, looming over the roof of the house, the distant hills, brown and parched from the prolonged drought, something that all the Yankee dollars in the world cannot fix. As my mother’s off-key humming fills up the morning, I find myself wondering what I would say if tonight, when she crawls onto the spot beside me on the mat we share, she asks me how I really made all that money. What would I say?

I think maybe I would close my eyes and picture myself as the girl on the beach in the leopard bikini with two diamonds in my ear. And, above the sound of crickets chirping outside our window in that vast country night, I would tell my mother what she wanted to hear. There in the dark I would whisper, “Ma, the Lord moves in mysterious ways.”

MARLEY’S GHOST

by Kwame Dawes

There is a man in a room with walls lined with old newspapers. That is the most reliable thing that can be said. A small room in a two-bedroom bungalow in a small development called Ensom City, just outside of Spanish Town. A characterless house in a neighborhood where hardworking folk—cement and garment factory workers, policemen, soldiers, chauffeurs, low-level civil servants, and enterprising street vendors—make a basic living. He has abandoned the island, the town, the district, the neighborhood—and the rest of the house—for this room lined with newspapers. They make the place look like a gift cheaply and hastily wrapped on the inside. They are already ochred with age; the colors on the comic sections faded.

The air in this room is old. Nowhere to go, it festers into a stink, the smell of a human being undecided about living or dying and depressed enough not to care about the smell. The moisture from sweat and breath hangs in the air like a despondent fog.

The man has been lying on the single bed in the room, on the same sheets, for days. Sometimes he gets up and walks around, a tall man who carries himself like a person who has suddenly lost a great deal of weight, with the unnecessary expansiveness of someone who has been told that he is smaller than he really is. Perhaps it is the airiness of his clothes or slowness of his movement, but something about him is in contradiction. It would not be surprising to hear him say, “I feel like I am in someone else’s body.” But he does not say this. What he says is, “She bound to come back … the bitch.” There is no drama in the way he says this.

He scratches his unkempt hair, wincing at the tenderness of his scalp. Then he runs his hands across his face, his scraggly beard—a peppering of tight curls over his gaunt jaw. His skin has the quality of deep tanned leather stained with dark polish. Hair grows on all parts of his body—long, thick, gleaming strands on his arms, his shoulders, his toes, and his ears. His beauty is the subtlest of things. It arrives long after you have seen him and dismissed him as strange. But when it arrives, it overwhelms you with its certainty—it startles you with the brilliance of an unexpected smile.

He gets up occasionally to hunt down some stale bread from the bottom cupboard of a cracked dresser, or to sip water from a rust-stained porcelain sink in the corner of the room. Sometimes he just stands up and touches everything in the room as if trying to remind himself that he is alive. A peeling chair, the cracked dresser with a large blank wooden frame where a mirror used to be, the sink, an olive-colored military sack, an unsteady bedside table with a massive boom box resting on it—he touches everything. A black telephone glimmers under the bed like a wet frog about to pounce. It has not sounded in days.

The room has one high window just above the bed, a window laddered by brown louvred panels. Little light comes through this window even at the height of the day because the thick foliage of a black mango tree crowds it, its leaves sometimes poking through the open louvres.

Strips of muted light pattern the floor—which is strewn with clothes and a plague of gutted oranges. There are easily sixty or more carcasses scattered around the room, peels curling, some turning brown with decay. Their tart scent complicates the smell of human waste. Tiny fruit flies hover like moving mist over the floor and the occasional green-bottle fly darts around the scattered clothes.

This is his cell. His hiding place. He has been in this cell listening to Exodus on auto-replay on the tape deck since his woman left him, his African-American woman who thought she could come to Jamaica and ride her way through difference, through a history that is nothing less than tortuous, through his chronic sense of failure. But she could not. She left. Now she is gone, he has been listening to Exodus, trying to consume himself with that inspired merger of politics and love, trying to let himself be lifted by the wisdom of the prophet. Those are the reliable facts. Beyond them nothing is certain. Beyond them hover the edges of his sanity and little is definite in that place.

He is lying on the bed, his face toward the ceiling. Forty years old—that is his age, although lately he has been losing count. These days he wants to start counting from 1945 instead of 1962. This confusion consumes hours of his day. When he can stop thinking of his woman leaving him, he starts to think of the year of his birth. Now it is February 6, 2002. He thinks he should be dead.

Sounds come from outside the room. Sounds of a city determined to pursue its Third World rituals of laughter, dubwise, gunshot, car crash, screwing, hallelujahs, praise, and the telling of stories. The world goes on. A man’s woman has left him. She has left him to travel back to America where she came from. He has driven her away. The world outside does not find this narrative especially remarkable. Women come and go. The world outside does not know this man, does not care about this man. The world outside does not care that this man has been in his room for six days eating oranges and trying to decide whether to take his medication or not. His woman has left. She may be pregnant. He is not sure. He wants to follow her but he doesn’t know what he would say if he did catch up with her. He could sing a song, ask her if this is love he is feeling. He thinks that if he could sing that song, if he could conjure up the spirit of the man singing the song in his head—a short, skinny man with a head full of flowing natty dreads and a cocky sense of entitlement to the love of a woman; any woman, all women—if he could muster up that fiction, perhaps the people outside would care that he is locked up in a cell trying to decide whether to take his medication or not. But he has stayed in the room, eating oranges and slowly stinking up his cell with his wasting self.

He does, though, dream.

He dreams his story. He is a creature of dreams. To enter his mind would be to enter a world of muted light and dreams. The tumbling of dates—1962, 1945, 1981, 2002—and the narrative of borrowed histories are the swirl of uncertainties that stir up his dreams. In his mind, he has a narrative that extends beyond that which he can own or even claim as history, as truth.

So this is all that can be called reliable: A man is in a room filled with orange peels and filthy clothes; Exodus repeats itself on the boom box; his woman has left him and he is not sure what to do. So he sleeps and dreams and becomes. This much we know.

2.

&nbs

p; At dawn—it was always at dawn—he felt that he had died and was now waiting to understand what that meant. At dawn, a dew fresh dawn, he would walk out into the halflight and look at the world. Then the world was not so certain of its separateness from the spirit world. Indeed, on such mornings, he could see beyond the earth, beyond the trees, beyond the sky, see into the mist, see everything in spirit and in truth. At dawn, the world was unconvinced of its mere earthiness. The world seemed completely different and he felt as if he had died at least once before. It was as if, during the night, while he was lying there in his bed, his body had curled into itself as if he needed to make space. He had curled into a tight ball as if he had never left the one-room apartment on First Street where, thirty years before, he had to share the small bed with Spider, his cousin. It was as if he had to make space for another body on the bed.

After stretching, he planted his feet on the cool tiles, then walked out onto the back porch to stare into the hills, trying to remember something, still feeling as if he was sleeping, feeling as if he should be somewhere else.

This is what it had been like since his return to Jamaica. He had been away for eighteen months. It was the first time in a long while that he had been away from home for that long, in one stretch. The travelling had been hard. Cold. He missed the yard, the gathering of men in the yard to kick some ball, to sit down and chat pure foolishness. He missed that. He missed the arguments about nothing. He missed the studio filled with smoke and the echoing of music shaping itself. He missed that. He missed the taste of the air, with its dust, with its stench of dead things. He missed eating an orange, pulling on the tart sweetness, or sucking on guineps, missed the taste of their slippery seeds, the flesh bright in his mouth and the tiny cups of green skin scattered around his feet along with the carefully stripped seeds, white with only the barest hint of pink flesh on them. He missed the sun on his back. The sun on his skin. The way the heat would come on him.

He had looked in the mirror after a few months abroad and had begun to feel white, to feel as if he was losing definition, his sharp edges. He felt as if he was losing himself in the mute gray of Babylon. He hated it. He spent most of his time indoors, in the studio, pretending to be writing songs, making jokes with the musicians who were on tour from Jamaica. But he was in mourning. That is what it felt like.

When they told him that his assassins had been found and that they were to be tried and executed, he did not hesitate. He would go back.

Three men came up to Babylon from Jamaica to get him. Three men no one would have dreamed could sit on a plane together. Two were serious generals of the street who had shed much blood in their battles against each other. The other, the third, was a longtime hustler, a man who had never sacrificed the independence of his criminal lifestyle for politics. He was very careful about that. He was a gunman, a robber, a t’ief, and he was going to rob whoever came along, and he did not give a rass whether they were Labourites or Socialists. He was a gleeful informer and the only reason he was alive was because of his firepower. But many had tried. Few wanted to associate with him. He was a genuine mafia man. That was who he was.

The three Magi came to the house to tell him that the two men who had come to execute him had been found. Joseph sat with them around a table to talk. The whole thing was a charade. They all knew it. Joseph knew it, but it was a ritual that had to be carried out. They came to tell him that it was now safe for him to go back. Joseph did not know anything about the two men they were holding. He did not know if they had anything to do with the shooting. They asked him, they repeated the names, they described the men. He knew nothing of them. He had not seen their faces as they fired bright sparks of light from the shadows of the mango tree in the yard. He had seen nothing.

But he knew that the Magi had a lot to do with the shooting and if they came to talk peace to him, if they came to tell him that it was safe to come home, then it meant that it was safe for him to come home. If they claimed that these were the ones who did it, then it was enough for him. But the ritual of atonement had to be carried out. The ceremony. The execution. It would take place in Kingston and Joseph was to be there. And Joseph, gong as ever, said he would be there, for peace was all he cared about. Peace and justice.

He returned to Jamaica and watched them hang the two men. He stood and looked the men in the face and watched them hang. Then he left the ghetto in a BMW and drove to his house uptown. He stepped into the dusty yard and sat on a stone under his special hibiscus grotto. He sat there and no one came to say anything to him. There he filled his head with the dizzying relief of smoke that helped him reach for somewhere else. He was home.

Death was familiar.

He had watched the men hang and had seen their spirits leave their bodies. But the spirits looked thoroughly confused. They had no idea where they were supposed to go. Someone was going to bury these bodies, but would this person know to light candle and hold a nine night to tell the spirits where to go? Joseph had been comfortable with the familiar taste of death, but not simply as a physiological truth, but as spiritual truth—something that went beyond the body failing to breathe again. He knew, though, that something integral had died in him as he watched the stinking fear of the two men, and smelled the shit and sweat of their writhing bodies. He had chosen to stand and look. Carried by the tyranny of his reputation and the weight of his responsibility as a tough man, he had chosen to watch. But it was more than that—it was curiosity and a peculiar desire to defy death by staring at it. He watched the men die and imagined his own death. It had been an impossible decision to make, but he had made it. Now, something had expired in him.

So he smoked his pipe in his backyard and then walked into the house to sleep. He slept.

Now morning was upon him. The radio was chattering. He looked out into the slight mist and he felt that he was dead, that he was in another world. He walked onto the porch and looked at the hills. The hills looked back at him. Then he made his way across the lawn in the backyard to the cluster of ficus berry trees at the end of the yard.

The roots coiled and twisted on the ground in a network of loops and crosses. Thick roots, smoothed and worn by rain and sun like the branches of a tree. They tendrilled their way to the thick trunk of the tree. It shot up straight, chunky like the neck of a boxer, and then spread, as if to mirror the net of roots, into a canopy of thickly leafed branches. The spread of the branches was impressive, a full wide stretch making a circle of shelter. The orange berries would fall and roll under the roots, accumulate and form a carpet of orange along the ground. Some rotting, some hard with sunlight, some still freshly crisp.

He sat among the roots and felt his body going back to sleep again. The sun crawled across his skin. He was home. Around him he heard birds and insects, but he could also hear the traffic, the seepage of radios beating out a medley of reggae and the lilt and drop of radio hosts arguing with callers.

They say prophets, true prophets, are able to prophesy their own deaths. They say that God speaks to them and assures them that their time is coming. Sometimes they argue, but always, always, true prophets know.

Joseph had seen the way those two men had died, and while he did not know of the cancer multiplying itself from his toe to his bones, to his blood, to his brain, even as he lay there staring at the sky, he knew the weightlessness of being weary of the world—the hollowness of having spoken all that was burning inside his belly. He felt dry, spent. When prophets grow silent it means they have served their purpose.

He could not see the future—that he would be leaving Jamaica again in three months to go on tour, flying late at night to New York to fill Central Park with skanking white folks, to then collapse, pale and trembling, his skin pallid like dead flesh. He could not speak of the journeys from doctors to doctors to herbalists to visionaries, or of the long, bone-aching flight to that small village in Germany. He could not know that women would soon be his keepers.

He had slept out in the open for several nights

and he was beginning to lose track of the days. The sun came up and went down.

He moved among the trees as if in a dream.

3.

In the middle of the night he wakes up expecting to see a wide-open sky with the dusty scattering of stars framed by the dark shadow of mountains. But all he sees is a blank grayness of walls around him. No. He was in a room, but this room is so small, with walls so close to him he cannot breathe. He wonders how he has gotten here, gotten to this place with walls covered with newspapers, a room that does not smell like the disinfectant-neat room of sunlight and white sheets where he had fallen asleep. Instead the place smells of an unwashed body, the funk of rotten flesh and the heavy musk of human waste, and the peculiar tart scent of rotten oranges. He opens his eyes and begins to feel meaning crawling toward him—the hint of a narrative that he knows to be an explanation for what he is seeing and smelling.

The logic creeps nearer, the way a dream fades away and waking insinuates itself on the mind. The meaning of the smells comes in small spurts of revelation—first the pressing need to get up, to take a shower, to call his aunt and ask her for money, to ask where his woman has gone and if she will come back. And the memory of his woman—whose name he sometimes forgets because it is too painful to call it—hits him hard. It fills him with such a terrible sense of panic that he turns away from the thought and tries to bury himself in another flight, another memory. He can tell in those brief moments that he is running. He can tell, too, that he is dying an inglorious death. He knows that if he were to simply get up, walk over to the cracked wood cabinet, open the dark brown plastic bottle, and pour out three pills, if he were to take those pills and sit on the edge of the bed waiting for them to slow everything down, waiting for them to bring him back to the gloom of his reality, he would probably understand everything happening in him and around him.

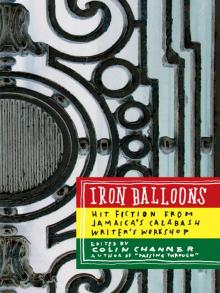

Iron Balloons

Iron Balloons