- Home

- Channer, Colin

Iron Balloons Page 10

Iron Balloons Read online

Page 10

Now you might say I’m being harsh or that a girl might have inclinations, but that don’t mean they have to come to light. You listen to me right now. You have grown men who could see these things in young girls before the girls see it themselves. And these men use to make it a point o’ duty to go up to the plazas and prey on aimless girls. Friend them up. Buy jumbo malt for them at Woolworth’s. And soon after that now, they start to give them little things. Little earrings. Little chaparitas. And tell them to tell their mother and father lie that they school friend give them for they birthday. Then after that now, they start to give them car drive. Pocket money come later. Then when the child least expect it, they start to pressure her for sex; and nine times out o’ ten, they give in.

Now, you use your own brain and sift what I just tell you before you answer. If a girl sleep with a man because him give her things and money, is not a prostitute that?

Yes, professor … I see you giving me the signal again, but I can’t stop now. I have to go on. Bear with me. Bear with me. This thing is too important. Way beyond this class.

My fellow classmates, that girl that Karen went to the plazas with, Claudia deMercardo, use to pluck out her eyebrows till all she leave back was a line. At the age of sixteen that girl already had a dirty reputation. She was—excuse me—a damn mattress.

I use to say to Karen when she use to ask if she could shave her eyebrow, “That look good to you? That look good? What sense they leave that line for? They no might as well just finish and done and just shave it off. What? They eye need a Parisian moustache?”

I use to talk to Karen about Claudia deMercardo all the time, because she was always asking Karen to ask me if she could spend the weekend at her house. Her people was real money people. They use to own in-bond stores and gas stations and a car distributorship. Where they use to live had everything, from pool to tennis court. And as far as I knew, people with that kind o’ money never really like people who black like me, especially when they think they white.

So whenever Karen ask me if she could go up there, I use to tell her no. Any parent who allow their sixteen-yearold daughter to do her eyebrow like that is not responsible. They’re slack! And slack parents make all kind o’ slack things go on in their house. Next thing you know, they allowing Claudia to drink, and have boys coming there and all those kind o’ things.

Listen, man. Let me tell you something. Boyfriend and that kind o’ thing couldn’t work in my house. Boyfriend? For a girl in school. University is a different thing. That time they’re grown. But high school? You must be mad!

I use to instill it in Karen every day: “Don’t put man on your head. Put your books.” I use to remind her that Claudia deMercardo and those fair-skin girls she know from school don’t have to pass no exam to get ahead in life. As soon as they finish school their parents giving them a job in a business. And even if they do start from the bottom, in two twos they reach the top, regardless of qualification. I told Karen, “They not like me and you! People like me and you must have a profession.”

But at the time she didn’t want to listen to me. She wanted to follow fashion. She wanted to act like she was carefree, as if she didn’t know is me alone she have to make everything work for her, and that if I slip, she slide. She wanted to rebel.

You know I had to wait for Karen for a hour? You hear me? A hour. I kept on saying, “Lord Jesus, I wonder if something happen to Claudia and Karen.” Because I couldn’t believe that Karen would do that to me, when she know I only have my lunchtime. And is not like now when you have cell phone and can call people and say you’re running late. In those days, if you late you just late, and by the time you get to where you was suppose to be, everybody face done make up a’ready, and everybody jump to their own conclusion. So it don’t even make no sense you try explain.

So in my distress now, I pu’ down my forehead on the steering wheel, and my mind just drift away. Then all of a sudden, Roger touch me on my back and say, “Mummy, Mummy, Mummy, see Karen there.”

When I look up I saw her running fast across the hockey field with her short plump self, her blue skirt and cream blouse dark with sweat. I don’t know where the blue tie was. She must be take it off. Claudia was right behind.

When the deMercardo gal see me now, she slip off one side and leave her friend to come and talk to me alone. Now what kind o’ true friend is that?

I said to Karen, “You don’t consider me?”

I said it so softly I could hardly hear myself. The tree was next to some tennis court, which was right beside another court where some girls was playing netball. And anywhere you go netball girls always loud.

She didn’t answer, so I asked her again, and raise my voice a bit. Same time now, the girl I ask for Karen when I just drive up, come up to my window and say, “Oh, you find her.” Then, before I could answer, she ask a question. But it really was a comment: “You’re Karen’s mummy’s friend?”

I say, “No. I’m Karen’s mother.”

She squint up her eye and look at me good, then she put her head into the car a little bit and take a look at the boys.

“Oh.”

Then she gone.

I knew what she was thinking—how I could be their mother and be dark like this? Well, the answer is that their father was a red man. He looked like a Puerto Rican in his features, but he had brown hair and hazel eyes. In just color alone, in certain light, you could make mistake and call him white. And you know something? That’s the only thing he ever give those children—a fair complexion to make things a little easier for them in life.

Anyway, when the girl left, I say to Karen, “Missis, beg you just get in the car.”

And you know what she said?

“When are you going to get off my back? Why’re you always harassing me? I’m like a prisoner. I can’t go anywhere.

No matter what I do, no matter what I say, I can’t be right. Just leave me alone, Mummy. Just leave me alone, man. Just lef’ me, Mummy. Just lef’ me. You think I don’t know why you going on like this? Is because you see me with Claudia, and you don’t like her. Why you always going on like she do you something? Is what she do you, Mummy? Is wha’ she do you so? Well, you know what? I don’t even care. Because Claudia is my friend. Right? Claudia is my friend. But you just don’t want me to have any friends. I don’t know why? I don’t know why? Well, she’s my friend, Mummy. She’s my friend. See it there. She’s my friend … and you better believe that dirts. And as a matter of fact, I don’t care what you or anybody else have to say. Claudia is my friend. Claudia is my friend. And who don’t like it, bite it.”

I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t say anything. I don’t even know if I did want to say anything. Perhaps if I did say anything, I would just sound like a fool.

She got in the car and slam the door. I had turn off the engine to save gas, so when the shame take me and I try to leave, the car couldn’t move off. Pure confusion take me. I confuse so till I forget which way the key suppose to turn. You see my distress?

While I there fumbling with the key, every now and then I take a glimpse through the window at the girls under the tree, and I see them watching me with their fair-skin self. They acting like they not looking, you know. But every time they see me look, they cover their mouth like they eating banana chips, or act like they tired and cover their mouth like they going to yawn. But they never cover their eyes though, and when I look at them I see pure laughing. Some o’ them was even running water.

So we on the way home now, and Karen is sitting in the front seat, and she just can’t keep still. She have her school bag in her lap and she hugging it up like is her boyfriend, or like she have something in there to hide. And so she moving, so she snorting. You’d think she was a bull. Bouncing back against the seat. Bracing her shoulder on the car door to get away from me. Sweating. Trembling. Breathing hard.

To tell you the truth, that’s normally the kind of thing I would just box her for. Before that she’d done one or two l

ittle rude things, back-answering and the like. And sometimes I use to have to give her a box for that. But this kind o’ bad behavior she was showing now was just a different type.

I had to drive on Constant Spring Road by the plazas to get home—it wasn’t a one-way then—and as I drove I heard a voice saying in my head, You can’t make children rule you, you know. If you don’t control them they wi’ break away. And when they break away, you can’t always catch them back. That’s when they end up worthless.

Listen to me, when a boy end up worthless is bad and not too bad. But when a girl end up worthless is a different thing. You can talk what you want to talk about equality, but with some things you have to accept that is just so life go.

Let me ask you something: If a girl waste her time and end up leaving school without any skill or education, or any way of getting ahead—let’s say a job with prospects, or acceptance to a college, and let’s say all her friends from school move on—you think that girl can feel good about herself? She might seem happy-go-lucky, and her face might always have a smile, but something else is going on inside.

When a girl begin to feel worthless is a easy thing for her to start act like she worthless in truth. She start to lose her confidence. She start to need attention, especially from men. And this make her start to dress and act a certain way. And when that happen, men just start to take advantage, start to full up her head with lie, cause they know from experience what she want to hear. You see, when that happen, before you know it the girl start bouncing round the place, and she might even feel as if she having a lot o’ fun. But to them she’s just a mattress. A place where they lie down and get relief. And from that, is just a matter o’ time before she breed and the bastard children start to come with more than one last name. Of course now, she can’t mind them on her own, so she need the man them for support. And you think they going give her support unless she give them back something? And if you give your body for money, you is what?

So all along the way, Karen going on like how I tell you—with her bad bull self—and even with what the voice was saying I couldn’t find the strength to discipline that child.

Because let me tell you, I’m the kind of mother who will discipline a child anywhere anytime. I don’t like to do it. But if I have to, I will.

If I gi’ you the look, and you act like you don’t see it, then I sneak up on you and gi’ you the pinch. And if the pinch can’t stop you, you getting something hot on your behind. Who don’t hear must feel.

But looking back at it now, I’m not even sure if is strength I didn’t have. I think I was just confused. I was just in disbelief. I never thought my daughter had it in her heart to talk to me like that.

When we get home, she come out o’ the car, and instead o’ opening the gate so I could drive in, she open it just enough so she could walk through by herself. So Roger jump out quick time and open out both sides.

To tell you the truth, until that happen I didn’t even remember that the boys were in the car. They were so silent. I wasn’t even sure who was driving home, who was really at the wheel. Because it wasn’t me. If it was me then it was only partly me, because I didn’t feel as if the whole o’ me was there.

I left the children with the helper, Miss Noddy, and spin round same time to go back to work. When Miss Noddy was closing the gate, I saw Mrs. Lee Yew watering her lawn across the street, and I remembered to ask her to make an appointment with her husband about Roger’s eyes.

I couldn’t concentrate when I got back to work. Luckily for me, it was the middle o’ the month, so the work wasn’t heavy that day.

There were twenty-eight of us in the office. Most of the others use to work in a open area with nothing to part the desks. A smaller set use to work in twos and threes in some little office separate with glass sheets, but they didn’t have a door. Only me and Mr. Parnell had a office with a door. He needed one because he didn’t have a manager. He use to run the place himself.

At around 4 o’clock, the office maid came into my office and ask if everything was okay. Miss Minto was her name. From she see me lock the door, she know something wasn’t right, cause I wasn’t the sort o’ person use to lock up myself. Anybody could come inside my office anytime. Same thing at Macy’s today. Ciselyn? She’s Miss Open Door.

So anyway, when Miss Minto ask me how I was, I told her everything was fine, but I was begging her a cup o’ tea.

Although I can’t take the smell o’ cigarettes nowadays, I use to smoke a lot that time. It started when my husband use to come home drunk at Deanery Road and mess up himself—sometimes the soldier uniform too—and I use to have to strip him off and clean him like a baby. I use to smoke to kill the smell.

When Miss Minto bring the tea, I went and stand up by my window, which was right between two big bookcase. I had a ceiling fan in the office, but I couldn’t turn it up because it would blow all the papers around the place, and I couldn’t open the windows fully cause the sea breeze would be worse. So the office was hot and had a salt and dye and leather smell.

I start to daydream now. Is so long ago I can’t remember what exactly was on my mind, and then my eyes drop on the parking lot below me, and I saw the spot where I approach Mr. Parnell years before. I see my car, which use to be his car. I had every reason to feel proud o’ myself, but all I feel was shame.

After a while I put my forehead on the window, then ease round and lean up with my back against the bookcase. I use to like collecting pretty calendars, and I had one from China on the wall. It was one o’ those that was a big poster with the months in a pad on the bottom, and when you finish a month you just tear it off. They had a pretty girl on the poster part, and she had a pretty fan. I use to always like to look at her. I don’t know why. Maybe it was just because she use to look attractive. There are some people whose personality just shine in the way they smile, and even when you see them in a picture you can know they nice. And she was one of them. So sometimes when I was feeling down or something, I would smile and look at her. My little Chiney friend.

So anyway, I get tired o’ looking at her, and to be frank, she wasn’t doing anything to ease my mind, and I find myself looking through the window again, smoking up the glass. Every time I blow, everything get cloudy and I feel like I could hide away, then the smoke get thin again. And the ashes? I just kept dropping them on Miss Minto floor.

We use to say the floors belong to her cause it was she who use to go down on her knee and take the coc’nut brush and clean them once a week. All we use to do was tramp on them. They use to say the office people use to walk and stomp because we never use to have to buy no shoes, for Mr. Parnell use to give us half a dozen pair every year.

Anyway, as I was thinking of Miss Minto and her floor—is like something come to light—I realize what was bothering me. Yes, it had to do with Karen, of course, and her behavior. But the thing itself that was depressing me was how she talk to me—like how most people talk to their maid. Is like she feel like she could talk to me anyhow and nothing wouldn’t come out of it cause I don’t have any status in life. Like I’m just this little dark girl who is right where she start out, and don’t reach nowhere, like I not good enough to be her mother.

As I start to think of this, I start to notice my reflection now. I could see it when I did a little thing with my eye.

In those days, I use to part my hair in the middle and flip it up like Doris Day. But it was hard to manage, you see. I had to press it every Friday evening. If I miss a Friday, it would get coarse and unruly, and all the straightening would come out. I look at my cheeks, and they look so hard, so—what’s the word again?—pronounced, even though I dab a little rouge on them. They look so unladylike, so tough. Then I begin to examine my nose. For all the times I use to clamp it, it was still the same … spread out like a van run it over, or a big truck lick it down. And the blue eye shadow? It only advertise how I was black.

Jesus Christ, I thought, you know you really, really black? Why you bothe

r even try with makeup base? That kind o’ black can’t hide. You black like doctor never take you from your mother belly. Like him grab you from a clinic that was burning down …

And when I take in all of this—you tell me, what I could do but cry? So that is what I did. I smoke my Benson in my brown skirt suit and think about my daughter, then I look at myself … and cry.

Later that evening, while I was working at the Pegasus, Roger called to sweet me up. Poor little heart. When the switchboard put him through, he told me that he need me to help him with some homework for his English class.

Now, Roger don’t call me at work unless is something important, and him never need me to help him with his homework yet because Andrew was always there to help. Plus, on top of that, he was extremely bright—passed his exams for high school from grade four, when most kids took it in grade six. And in any case, most of them who take it didn’t pass. Karen was one o’ them. She take it three times in a row and fail.

So I ask him, “What’s the composition about?”

“Well … Mummy … my teacher asked me to write a composition on a work of art.”

“Lord. So now we have to go to National Gallery?”

“No, Mummy, because I selected you. You want to hear what I put in there already?”

I start to smile now.

“Yes.”

And then my bubble burst.

He said, “My mother is a most resplendent example of God’s imagination. He made her more beautiful than all the creatures. My mother’s beauty is special. Do you want to know why it is special? Most people’s beauty is on the outside, but that kind of beauty is only skin deep and will not last forever. My mother’s beauty is of the permanent type. Her beauty is on the inside, and that is the kind of beauty that will always last. How does that sound so far?”

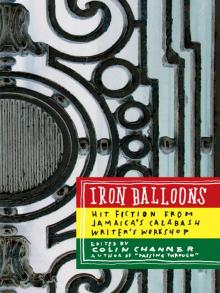

Iron Balloons

Iron Balloons